In early 2010, I was sitting at a communal table in a coffee shop in Cape Town, when I spotted a grizzled, bearded fellow who looked strangely familiar. It was Athol Fugard, South Africa’s foremost playwright and the great chronicler of his country’s apartheid past. There he was, sipping a cup of coffee like any ordinary person.

I plucked up courage and approached him, murmuring something inarticulate about my admiration for his writing. “Hall-O,” Fugard said enthusiastically. “Join us. Have a coffee. Or a glass of wine.”

One of the great things about Fugard, who died on Saturday, was that he was an ordinary person as well as an extraordinary one. He was wonderfully enthusiastic about people and their potential, ready to see the good in every situation, but also unafraid to confront the bad, both in others and himself. The famous scene in “‘Master Harold’ … and the Boys,” in which the young white protagonist spits in the face of his Black mentor, was, he freely confessed, drawn from his own life.

As the theater critic Frank Rich noted in a 1982 New York Times review of the play, Fugard’s technique was to uncover moral imperatives “by burrowing deeply into the small, intimately observed details” of the fallible lives of his characters.

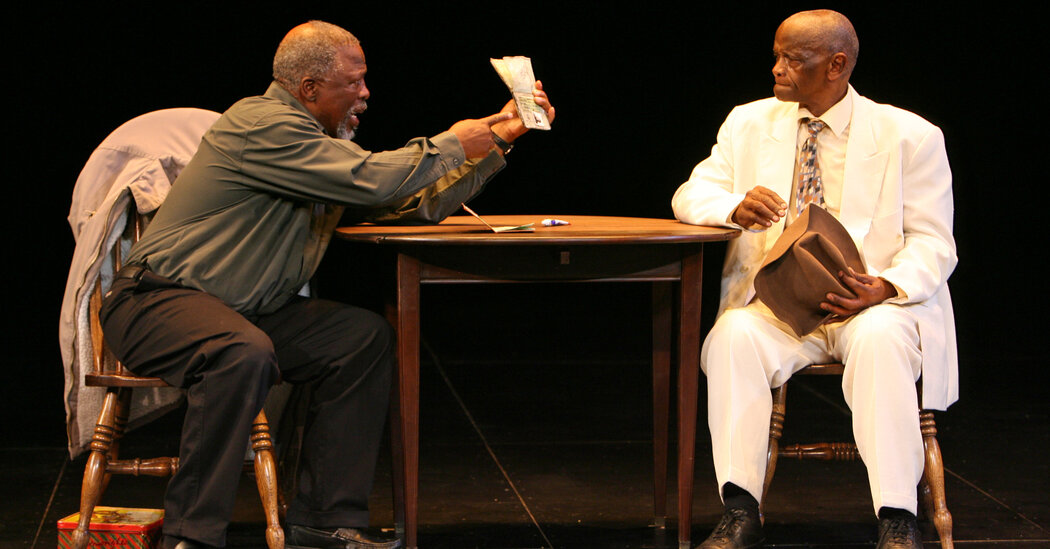

My first encounter with Fugard’s work was in the early 1980s, when I saw a production of his 1972 play “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead,” written with Winston Ntshona and John Kani. It’s a bleakly comic tale of a man who assumes another identity and assigns his own to a corpse, in order to gain the coveted pass book that the South African authorities required as permission to work.

It was a visceral, painful jolt to the soul. I grew up in apartheid South Africa. I knew about passbooks, about the police hammering on the door at night, about the dehumanizing, demeaning way Black people were treated. But the humanity and warmth of Fugard’s writing, the complex reality of his characters, made the cruelty of South Africa’s racist regime an excruciating truth.

In 2010, Fugard was living in San Diego, but had returned to Cape Town to rehearse a new play, “The Train Driver,” before its premiere at the newly built Fugard Theater, which the producer and philanthropist Eric Abraham had named after the playwright.

The Fugard, which was to become a vibrant beacon on the South African arts scene, was located in District Six, a formerly mixed-race area that was declared a “whites only” neighborhood by the apartheid government in 1966. (The theater, where numerous works by Fugard were seen over a decade, closed in 2020, a victim of the coronavirus pandemic shutdowns.)

“You will be sitting in the laps of the ghosts of the people who couldn’t be here,” Fugard said on opening night.

Fugard’s plays are in great part about those ghosts, an attempt to bear witness to forgotten and unknown lives and to the moral blindness and blinkered vision of the reality engendered and perpetuated by apartheid. His best-known works — “Blood Knot,” “Boesman and Lena,” “The Island,” “The Road to Mecca,” “Sizwe Banzi,” “Master Harold” — are mercilessly unsparing about the insidious way that race determines relationships in apartheid South Africa. But they are also deeply humane.

“Moral clarity — in such short supply in South Africa and indeed the world — was what he delivered,” Abraham wrote after the playwright’s death last weekend. “He pointed us to the boxes containing our past and urged us to rifle through them in order to learn more about ourselves.” Fugard understood, Abraham continued, “that divisions can only be overcome by a realization of a shared humanity, a palpable sense that we must look after one another if we are to make it through an often cruel and unforgiving world.”

Fugard moved back to South Africa soon after the Fugard Theater opened, first living in New Bethesda, where “The Road to Mecca,” about the outsider artist Helen Martins, was set; later he and his wife, Paula Fourie, moved to the university town of Stellenbosch. I met and interviewed him several times over the years; he was sometimes intense, but always jovial, unpretentious, humble.

Once he told me that he considered himself an outsider artist, without formal training or a degree, starting to write at a time when no one thought it worthwhile to put a South African story onstage.

But by being determinedly local, Fugard transcended the specifics of one country. As Abraham noted, his plays demonstrate the value of every human life. “Come over for a glass of wine,” Fugard would inevitably say at the end of an interview. I wish I had.